Item description: Illustrations accompanying the article, “Forts Hatteras and Clark” in Harper’s Weekly, September 21, 1861:

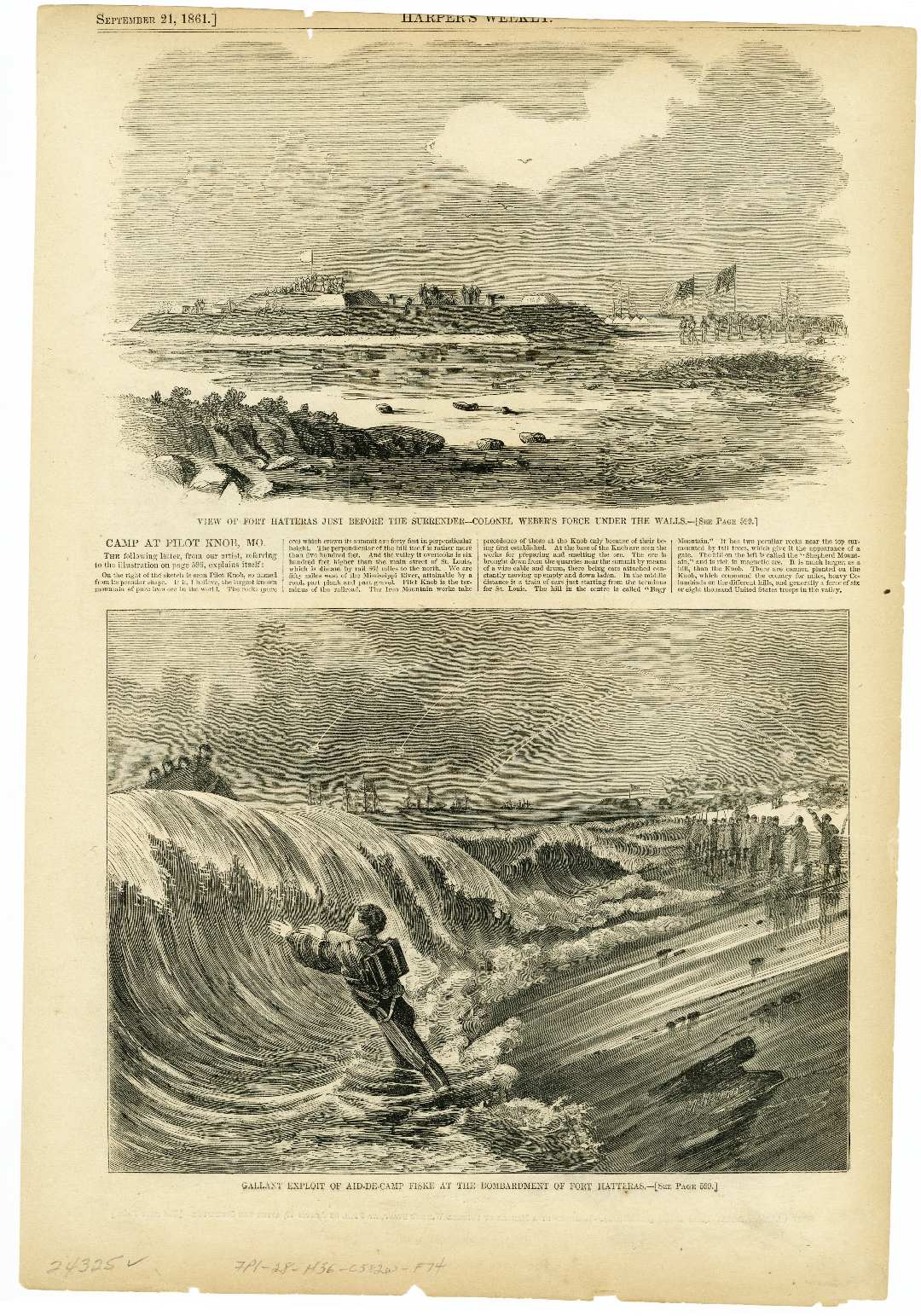

- page 597, “View of Fort Hatteras Just Before the Surrender—Colonel Weber’s Force Under the Walls,” and “Gallant Exploit of Aid-du-camp Fiske at the Bombardment of Fort Hatteras.”

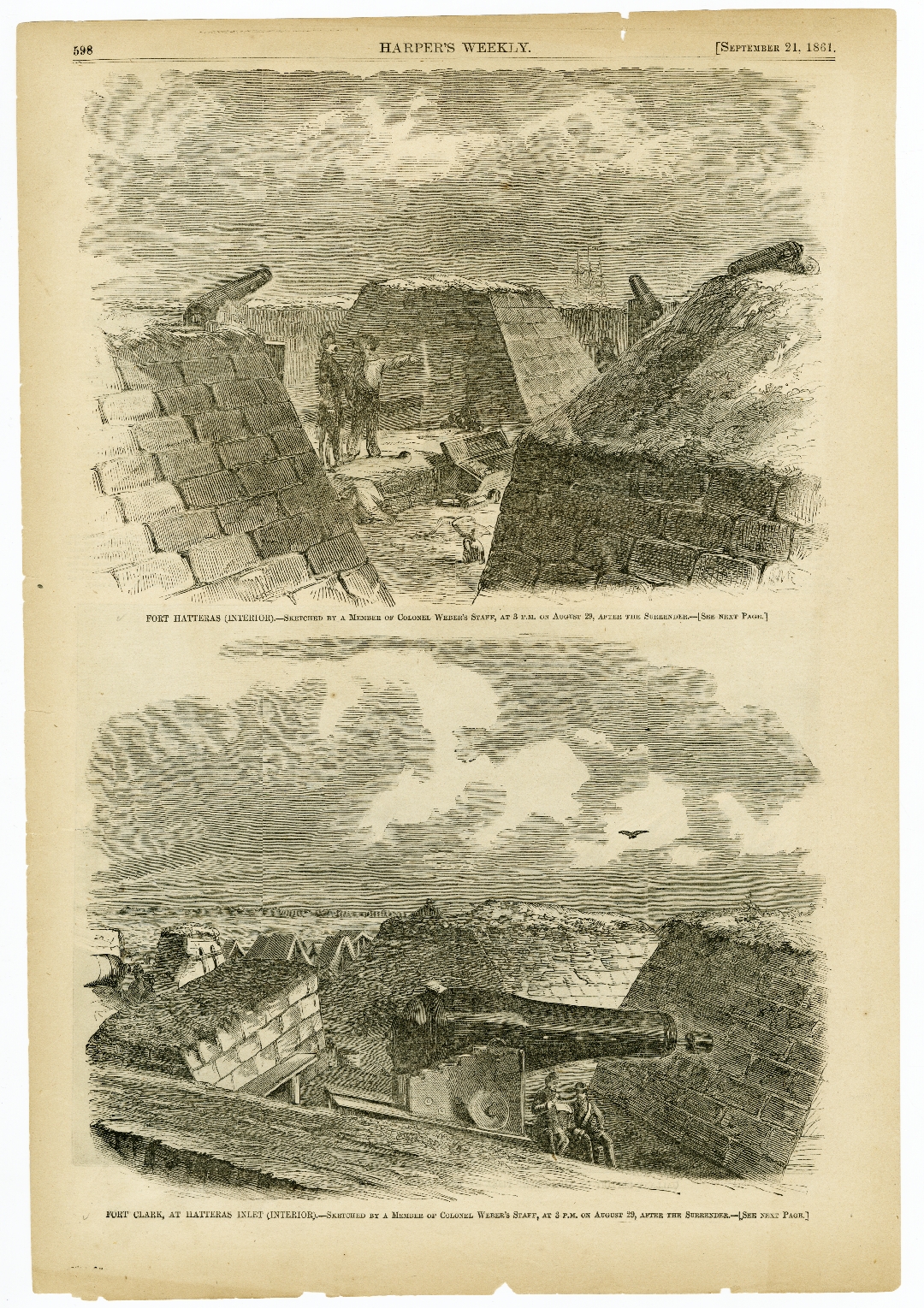

- page 598, “Fort Hatteras (interior).—Sketched by a member of Colonel Weber’s staff, at 3 P.M. on August 29, After the Surrender,” and “Fort Clark, at Hatteras Inlet (interior).—Sketched by a member of Colonel Weber’s staff, at 3 P.M. on August 29, after the surrender.”

Note to readers: the post for 27 August 1861 features the Currier and Ives illustration, “Bombardment & Capture of the Forts at Hatteras Inlet, N.C.”

Accompanying article (page 599):

FORTS HATTERAS AND CLARK

WE continue this week our series of illustrations of the brilliant achievement of Coln. Stringham and General Butler at Hatteras Inlet. On page 598 we give a couple of pictures of THE INTERIOR OF FORTS HATTERAS AND CLARK, from drawings made on the afternoon of Thursday, 29th, by Mr. Kaufmann ; and on page 597 we give AN EXTERIOR VIEW OF FORT HATTERAS, and illustrate the GALLANT ACHIEVEMENT OF LIEUTENANT FISKE, who swam through the breakers at the risk of his life to deliver General Butler’s orders to the forces.

Of the forts themselves the correspondent of the Tribune wrote:

Forts Hatteras and Clark were posts of great importance to the rebels, the former being by far the strongest and most extensive work, and correspondingly the most important of the two.

Their construction was commenced about three months since by the State of North Carolina, and were planned with a good deal of engineering skill, and were built at great expense of labor and money. Fort Hatteras covers an area of between one and two acres, and, like Fort Clark, was laid out by Colonel William Beaverhouse Thompson, of Virginia. It is an earth-work, mounting ten barbette guns, 32-pounders, live bearing toward the sea. It was designed to mount eight and ten inch Columbiads, but they do not seem to have arrived.

In the fort was a bomb proof, which proved, however, not to have been proof against our bombs; for a shell struck the top of the work, penetrated through the forepart of sand covering, and entered the apartment below, next to the magazine, with only a board partition intervening. It did not explode, however. Had it done so, the loss of life would have been terrible, as more than three hundred men had been forced and were closely packed in the subterranean chamber at the time. The shell filled the chamber or vault with dust and smoke, and the men supposing the magazine was on fire, a terrible panic ensued. The men ran out, and nothing that the officers could do, even their threats to bayonet and shoot them, could restrain the men within the fort. Shortly after another shell exploded on the bomb-proof, and it becoming evident that so accurate had become the range and firing of the fleet, the magazine would soon be exploded, and the white flag was hastily run up.

When I entered the fort, a considerable length of time before General Butler arrived, the interior was a complete wreck, and the wonder was that hundreds were not killed. They said that for the last half hour our shells, almost without exception, fell and exploded inside the fort. Two of the guns were disabled. The tents and shanties were a wreck, and there was scarcely room for the wounded.

The Herald correspondent thus speaks of Mr. Fiske’s exploit, and of its consequences: After the smaller fort had been silenced a boat was sent ashore with Mr. Fiske, aid to General Butler, who swam through the breakers to convey to Colonel Weber’s command the orders of the General and information of the intended movements of the fleet. Upon entering the redoubt called Fort Clark, he seized upon the books and papers found there; among them are official documents and the letter books of the commanding officers. Mr. Fiske strapped this package upon his shoulders and swam out again to the only boat that was left sea-worthy, and carried them to the General, who was thus informed of what was going on at the moment of the appearance of the fleet off the inlet. When the meeting was held on the Minnesota to arrange terms of capitulation, the rebel officers were utterly astonished at the accurate information of the General, and inquired anxiously how he knew what they were doing the day before, and who was the person among them to whom signals had been made from the fleet. The General simply replied that he possessed means of accurate information.

Hatteras Inlet is thus described in the Herald: A geographical sketch of the spot where our naval forces have been so triumphant can not fail to prove interesting to our readers. Situated about twelve miles from Cape Hatteras lighthouse is the inlet in question. It is known to the mariner by a low sand island, which was formerly a round hammock, covered with trees on the eastern side of the entrance. The breakers seldom extend entirely across the entrance to the cove or harbor, but at nearly all times make on each side, and between them lies the channel. The bar should be approached from the northward and eastward, and vessels should keep in four or five fathoms of water along the breakers until up with the opening. The least water on the bar is fourteen feet mean low water, and the rise and fall of the tide but two feet. Once inside the inlet the mariner finds good anchorage in a hard sand bottom, except a few sticky spots at the head of the channel. The anchorage affords protection from all winds except those from the southward and westward.

As an entrance to Pamlico, Albemarle, and Currituck Sounds, the possession of Hatteras Inlet is of vast importance to the cause of the Union. With Ocracoke and Hatteras Inlets closed, North Carolina may be said to be completely shut in from the ocean. Privateers can no longer be sent to sea through the Dismal Swamp Canal and Albemarle Sound to annoy our commerce.

Item citation: North Carolina County Photographic Collection, Flat Box 02, Folder P0001/0377; North Carolina Collection, Wilson Special Collections Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.